LAND BACK: A Movement, A Spirit, A Practice

By Erin Poor | Citizen of Cherokee Nation; temporary visitor on Pawnee and UMÓⁿHOⁿ and Očhéthi Šakówiŋ Land.

In recent years the phrase LAND BACK has gained popularity in mainstream culture thanks to the work of Indigenous activists. But it is so much more than a contemporary movement. It is a spirit that has endured and strengthened over generations, informed by the multiplicity of Indigenous resistance practices across the globe. It is a movement, but it does not answer to one leader. It is the coalescing of generational efforts, executed using a diversity of tactics, with one goal: getting the land back.

To better understand the issue, it is important to first call out different ideologies of human-land relations. In the current Western society, as has been the case since the beginning of the United States, land ownership and ownership of private property is a key component to life, policy, and economic prosperity. To Indigenous peoples, the concept of land ownership did not exist before the United States. Rather, Indigenous peoples believed in land stewardship. This form of relationship indicates kinship between land, human, and other-than-human inhabitants. Many Indigenous peoples consider the land to be a part of Mother Earth, and one cannot own their Mother. Instead, Tribal peoples worked with the land in a collective way, with no one person having more of a right to the land than another.

Land was, is, and forever will be stewarded by Indigenous peoples. And it is these relationships of stewardship, beneficence, reciprocity, exchange, respect, and reverence that undergirded centuries of Indigenous knowledge of the land. Under Indigenous stewardship the land flourished. Animals and ecosystems were celebrated for their biodiversity. Balance was, is, and will be forever a core value. Since the dominant practice has become land ownership and resource extraction, this world has seen genocide and forced removals of people, the destruction of habitat and biodiversity, climate change, and what some scientists have termed the sixth mass extinction.

Though Indigenous people believe in land stewardship over ownership, we are forced to negotiate our rights and existence in terms more familiar to settler colonialism, i.e. ownership. LAND BACK as a movement seeks to transfer the ownership of land from non-Native to Native hands so that Indigenous people can resume their ancestral land-based practices and ceremonies, apply their ancestral knowledges of land stewardship, assert self-sovereignty, and achieve collective liberation.

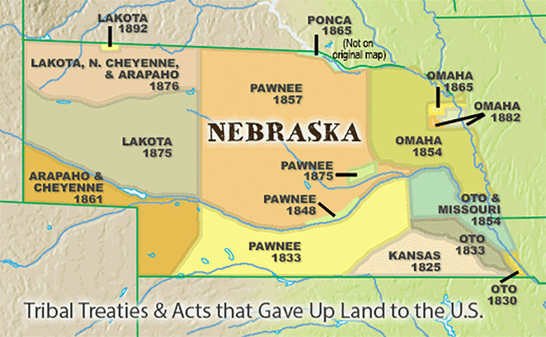

How does LAND BACK happen? In many ways. For one, Indigenous people are using legal means to pursue their right to lands granted by the United States through treaties. For example, “NDN Collective”, a nonprofit led by Lakota community leaders has recently reignited the fight for recognition of Lakota land rights and Tribal sovereignty in the Black Hills. Promised to the Lakota (federally recognized as the “Sioux Nation”) in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, the U.S. broke their treaty when gold was found in the Black Hills. That region, known to the Lakota as the Hesápa, is their sacred homelands. Though the Lakota never ceded that land, the United States claims ownership and American citizens occupy the land. Lakota leaders have engaged in several direct actions to claim their legal right to that land, some of which have ended with violence by law enforcement and arrests of Lakota people on their own land.

LAND BACK strategy also includes engaging with individual landowners and encouraging them to deed their land to the Native Nation of that region, or to individual Native Americans and their families. Families who benefited from policies like the Homestead Act of 1862, directly benefited from state-sanctioned genocide and forced removal of the Indigenous inhabitants of that land. Today, white people in America benefit from generational wealth and property that is only possible because of Indigenous genocide, removal and allotment policies of the 18th and 19th century. Landowners, who care to address the humanitarian atrocities of the not-so-distant past, have slowly begun deeding their land to the Native Nations who preceded them in that region.

Nebraska has seen a few examples of this kind of solidarity with Indigenous peoples. In 2007, Roger and Linda Welsch deeded 60 acres of farmland in central Nebraska to the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma (The Pawnee Nation’s homelands are in central Nebraska; they were forcibly removed to Oklahoma in the 19th century). The Welschs will live out their lives on their land, and when they die, the Pawnee Nation will be the legal owners of the land. More recently, in 2018, Nebraska landowners Helen and Art Tanderup deeded 1.6 acres of their land near Neligh, Nebraska to the Ponca Tribe. The Ponca Tribe has been able to cultivate their sacred corn on that land after it had been absent for more than 130 years.

Landowners can also choose to give land back to individual Indigenous people and families. To be Indigenous is to be of the land. Indigenous peoples need access to land for ceremony, to resurrect ancestral foodways, to rebuild kinship networks, to exercise self-sovereignty, and to heal the land. Even breaking off an acreage from a larger landholding to give to a Native family would have the power to change the lives of generations.

Other examples of LAND BACK have been seen on city and state levels. In 2019, the city of Eureka, California formally signed the transfer of lands on Duluwat Island back to the Wiyot Tribe. The island is sacred to the Wiyot people, and it had been stolen from the tribe 160 years ago after the people living on the island were massacred so the land could be used for a dairy farm. After decades of advocacy, the Wiyot people were successful in convincing the city to give them the land back.

Nonprofits and conservation organizations have also played a role in the LAND BACK movement. Within the last two years, the Nature Conservatory in Nebraska has given 284 acres of land to the Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska. The Iowa Tribe will establish a Tribal National Park, only the second of such parks to exist.

LAND BACK is not only the work of Indigenous activists, it is a movement that every single person can and should be a part of. By giving what you have, you can help be a part of this ongoing effort. You can donate funds to Indigenous peoples or Nations seeking to purchase land. You can deed your land to an Indigenous person or Nation, to use immediately or after your death. If you are a lawyer, you could help with the legal components of deeding land to Native peoples or Nations. If you are in business, you could educate your fellow community members about LAND BACK and the importance of Indigenous land stewardship. If you live in a city or town, you could advocate to your city leaders to deed back city lands to Native Nations or peoples. It can become a practice that you include in your weekly routine, or in your daily life.

A good place to begin is by understanding on whose homelands you currently reside. A website called Whose.land is a great resource. There is also an app called Native Land you can download to your smartphone. Once you understand whose land you are on, begin to find a way to be in right relation with that Nation and its people. It is your responsibility to learn the stories of removal, so you can understand the depth of historical trauma that lives on in Indigenous peoples and begin to make it right. LAND BACK is a movement, a spirit, and a practice that each of us can live daily. And if we live that, we can achieve the rematriation of land, the return to Indigenous land stewardship, and a healthier Earth for our future generations.

In recent years the phrase LAND BACK has gained popularity in mainstream culture thanks to the work of Indigenous activists. But it is so much more than a contemporary movement. It is a spirit that has endured and strengthened over generations, informed by the multiplicity of Indigenous resistance practices across the globe. It is a movement, but it does not answer to one leader. It is the coalescing of generational efforts, executed using a diversity of tactics, with one goal: getting the land back.

To better understand the issue, it is important to first call out different ideologies of human-land relations. In the current Western society, as has been the case since the beginning of the United States, land ownership and ownership of private property is a key component to life, policy, and economic prosperity. To Indigenous peoples, the concept of land ownership did not exist before the United States. Rather, Indigenous peoples believed in land stewardship. This form of relationship indicates kinship between land, human, and other-than-human inhabitants. Many Indigenous peoples consider the land to be a part of Mother Earth, and one cannot own their Mother. Instead, Tribal peoples worked with the land in a collective way, with no one person having more of a right to the land than another.

Land was, is, and forever will be stewarded by Indigenous peoples. And it is these relationships of stewardship, beneficence, reciprocity, exchange, respect, and reverence that undergirded centuries of Indigenous knowledge of the land. Under Indigenous stewardship the land flourished. Animals and ecosystems were celebrated for their biodiversity. Balance was, is, and will be forever a core value. Since the dominant practice has become land ownership and resource extraction, this world has seen genocide and forced removals of people, the destruction of habitat and biodiversity, climate change, and what some scientists have termed the sixth mass extinction.

Though Indigenous people believe in land stewardship over ownership, we are forced to negotiate our rights and existence in terms more familiar to settler colonialism, i.e. ownership. LAND BACK as a movement seeks to transfer the ownership of land from non-Native to Native hands so that Indigenous people can resume their ancestral land-based practices and ceremonies, apply their ancestral knowledges of land stewardship, assert self-sovereignty, and achieve collective liberation.

How does LAND BACK happen? In many ways. For one, Indigenous people are using legal means to pursue their right to lands granted by the United States through treaties. For example, “NDN Collective”, a nonprofit led by Lakota community leaders has recently reignited the fight for recognition of Lakota land rights and Tribal sovereignty in the Black Hills. Promised to the Lakota (federally recognized as the “Sioux Nation”) in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, the U.S. broke their treaty when gold was found in the Black Hills. That region, known to the Lakota as the Hesápa, is their sacred homelands. Though the Lakota never ceded that land, the United States claims ownership and American citizens occupy the land. Lakota leaders have engaged in several direct actions to claim their legal right to that land, some of which have ended with violence by law enforcement and arrests of Lakota people on their own land.

LAND BACK strategy also includes engaging with individual landowners and encouraging them to deed their land to the Native Nation of that region, or to individual Native Americans and their families. Families who benefited from policies like the Homestead Act of 1862, directly benefited from state-sanctioned genocide and forced removal of the Indigenous inhabitants of that land. Today, white people in America benefit from generational wealth and property that is only possible because of Indigenous genocide, removal and allotment policies of the 18th and 19th century. Landowners, who care to address the humanitarian atrocities of the not-so-distant past, have slowly begun deeding their land to the Native Nations who preceded them in that region.

Nebraska has seen a few examples of this kind of solidarity with Indigenous peoples. In 2007, Roger and Linda Welsch deeded 60 acres of farmland in central Nebraska to the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma (The Pawnee Nation’s homelands are in central Nebraska; they were forcibly removed to Oklahoma in the 19th century). The Welschs will live out their lives on their land, and when they die, the Pawnee Nation will be the legal owners of the land. More recently, in 2018, Nebraska landowners Helen and Art Tanderup deeded 1.6 acres of their land near Neligh, Nebraska to the Ponca Tribe. The Ponca Tribe has been able to cultivate their sacred corn on that land after it had been absent for more than 130 years.

Landowners can also choose to give land back to individual Indigenous people and families. To be Indigenous is to be of the land. Indigenous peoples need access to land for ceremony, to resurrect ancestral foodways, to rebuild kinship networks, to exercise self-sovereignty, and to heal the land. Even breaking off an acreage from a larger landholding to give to a Native family would have the power to change the lives of generations.

Other examples of LAND BACK have been seen on city and state levels. In 2019, the city of Eureka, California formally signed the transfer of lands on Duluwat Island back to the Wiyot Tribe. The island is sacred to the Wiyot people, and it had been stolen from the tribe 160 years ago after the people living on the island were massacred so the land could be used for a dairy farm. After decades of advocacy, the Wiyot people were successful in convincing the city to give them the land back.

Nonprofits and conservation organizations have also played a role in the LAND BACK movement. Within the last two years, the Nature Conservatory in Nebraska has given 284 acres of land to the Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska. The Iowa Tribe will establish a Tribal National Park, only the second of such parks to exist.

LAND BACK is not only the work of Indigenous activists, it is a movement that every single person can and should be a part of. By giving what you have, you can help be a part of this ongoing effort. You can donate funds to Indigenous peoples or Nations seeking to purchase land. You can deed your land to an Indigenous person or Nation, to use immediately or after your death. If you are a lawyer, you could help with the legal components of deeding land to Native peoples or Nations. If you are in business, you could educate your fellow community members about LAND BACK and the importance of Indigenous land stewardship. If you live in a city or town, you could advocate to your city leaders to deed back city lands to Native Nations or peoples. It can become a practice that you include in your weekly routine, or in your daily life.

A good place to begin is by understanding on whose homelands you currently reside. A website called Whose.land is a great resource. There is also an app called Native Land you can download to your smartphone. Once you understand whose land you are on, begin to find a way to be in right relation with that Nation and its people. It is your responsibility to learn the stories of removal, so you can understand the depth of historical trauma that lives on in Indigenous peoples and begin to make it right. LAND BACK is a movement, a spirit, and a practice that each of us can live daily. And if we live that, we can achieve the rematriation of land, the return to Indigenous land stewardship, and a healthier Earth for our future generations.

This article was informed by several Indigenous people fighting for their land and who embody the spirit of LAND BACK, including Felecia Welke, Corinne Rice Grey Cloud, Kanahus Manuel, Gord Hill, Enāēmaehkiw Kesqnaeh, and , NDN Collective. Wado.

Erin Poor, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, is an independent art historian, curator, organizer, grant writer, and public educator based in Lincoln, NE. Erin is a clinical mental health counselor in training, hoping to be of service to her communities.

Erin Poor, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, is an independent art historian, curator, organizer, grant writer, and public educator based in Lincoln, NE. Erin is a clinical mental health counselor in training, hoping to be of service to her communities.